Spotlight on Members

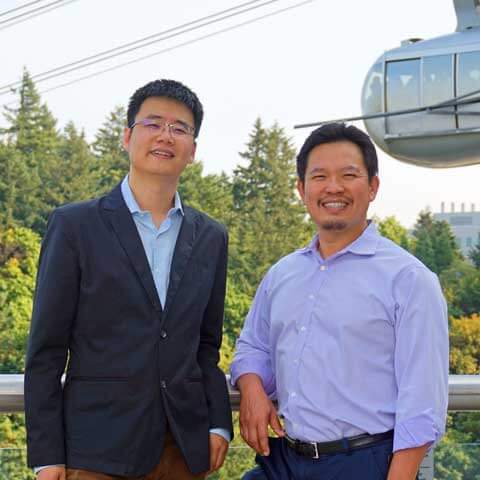

2017 Dr. David L. Epstein Award presented to David Huang and Liang Liu

Clinician-scientist David Huang, MD, PhD, FARVO, was an engineer before he ever studied medicine. Huang, who is a co-inventor of the revolutionary optical coherence tomography (OCT), earned his undergraduate and graduate degrees in electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). “I always thought I should pick a specialty where my engineering and quantitative skills would be useful,” he recalls.

Clinician-scientist David Huang, MD, PhD, FARVO, was an engineer before he ever studied medicine. Huang, who is a co-inventor of the revolutionary optical coherence tomography (OCT), earned his undergraduate and graduate degrees in electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). “I always thought I should pick a specialty where my engineering and quantitative skills would be useful,” he recalls.

He searched through several subspecialties before settling on ophthalmology, which became the obvious choice while he was working on the development of OCT, a non-invasive imaging technology that allows clinicians to see fine layers of tissue. As he and his collaborators were looking for the best clinical application of OCT, he worked in partnership with the ophthalmologists at Harvard Medical School and Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary. “I really enjoyed working with the ophthalmologists there,” he says.

Since completing his PhD at MIT and his medical degree at Harvard in 1993, Huang has been blazing trails in ophthalmic imaging as a clinician-scientist ever since. Huang now directs the Center for Ophthalmic Optics and Lasers at Oregon Health and Science University (OHSU) and sees patients at the Casey Eye Institute once a week. Though Huang considers himself a cornea specialist in his clinical practice, his clinical research spans across the eye, including glaucoma and retinal diseases.

In 2017, Huang added to his long list of awards and accolades when he and his mentee at OHSU, Liang Liu, MD, received the Dr. David L. Epstein Award. This prestigious $100,000 research award is given annually to a senior investigator who has a track record of mentoring clinician-scientists to independent academic and research careers. The award supports a collaborative project for the mentor and mentee related to glaucoma.

“In the early stages of glaucoma, cells are dysfunctional and have less metabolic need even before they die off and cause loss of tissue thickness. In the late stages, there continues to be a drop in blood flow and capillary density as ganglion cell function continues to wane, even when the remaining tissue are too thin to measure changes.”

Huang and Liu first met in 2013 as Huang was preparing to launch OCT angiography, an imaging technology that analyzes laser light to reflect off moving blood cells, giving a picture of blood flow through the vasculature of the eye without the use of dyes. Early studies saw good results, and the technology seemed ready for wider clinical studies. Huang recruited widely, including organizing an ocular circulation meeting in Beijing. That is where he met Liu who had just finished his ophthalmology residency and was looking for research opportunities in the U.S. “He was my first catch when I tried to launch OCT angiography in 2012,” Huang remembers. “It was very new then, and most people didn’t know what the heck it was. He was one of the first ophthalmologists to become interested in OCT angiography.”

With support from the Dr. David L. Epstein Award, Huang and Liu are examining the application of OCT angiography as a diagnostic and monitoring tool for glaucoma. OCT is currently used to evaluate the progression of glaucoma in patients, but it has its limitations as it can be difficult to detect glaucoma on an OCT image early and late in disease progression. “Structural OCT can measure the thinning of the neural fiber layer, but there is a lag between the onset of disease and neural fiber thinning,” Huang explains, meaning it takes time for glaucoma to become obvious on an OCT image.

OCT angiography, however, may stand a better chance of capturing the progression of glaucoma by looking at blood circulation instead of tissue thickness. “Theoretically, if you look at microcirculation, you should have a better measure of glaucoma at very early and very late stages,” Huang explains.

“In the early stages of glaucoma, cells are dysfunctional and have less metabolic need even before they die off and cause loss of tissue thickness. In the late stages, there continues to be a drop in blood flow and capillary density as ganglion cell function continues to wane, even when the remaining tissue are too thin to measure changes.”

Huang and Liu have been collecting data for the past year, and they have good data to support their hypothesis. Liu is completing his analysis now, and the mentor/mentee pair will present their data at the ARVO 2019 Annual Meeting during a special session. Huang anticipates they will be able to apply for a larger grant to perform a longitudinal trial to see if OCT angiography can improve the monitoring of glaucoma long-term.

The research funded by the Dr. David L. Epstein Award looks bright, so does the future of Huang’s mentee. As Liu looks to his career ahead, he plans to follow the clinician-scientist path and his mind is on new ideas and techniques to improve the long-term diagnosis of glaucoma. AJ

What makes a good mentee?

David Huang, MD, PhD, FARVO, who has mentored many young clinician-scientists, describes the key traits he looks for in a mentee:

Curious

Appreciate people who have a natural curiosity. “Good mentees are willing to explore their field of research widely,” says Huang. “They will follow the problems other people are trying to solve.” He also looks for people who have new ideas for research.

Well-read

His mentees read widely about their research interest to learn more about what others are doing. “Know where the cutting edge is,” he says. “Be aware of the solutions other people are thinking about and use other people’s intelligence to help solve your problems.” His practical tip for finding time to read? When you meet a deadline, instead of celebrating, go read!

Good communicators

Mentees are willing to talk about their work and describe their thinking behind a scientific challenge. “Some people are reticent to share what they are thinking,” he says. “That’s an impediment to me being able to help guide them through a challenge.”

Ambitious

Good mentees are willing to tackle new projects and not be too conservative in what they are willing to take on. “Sometimes projects don’t work out. You have to work on a few different things before you will hit a home run,” says Huang. “However, there’s a clear line between risk-taking and self-promotion. I like people who are ambitious, but I don’t appreciate people who devote energy to fighting for credit.”