Patients: From consumers to partners

Passenger. End user. Spectator. These are terms that many in biomedical research would use to describe the role patients play as a potential therapy winds its way along the development pipeline. Yet, a growing number of patients are no longer content to simply watch and wait as possible life-changing science happens without them.

“Other than providing funding, the patient community hasn’t traditionally been given the opportunity to interact with researchers, sponsors and regulators,” says Randy Wheelock, chief advisor for research and therapy development at the Choroideremia Research Foundation (CRF). “Patient advocacy groups have a lot to offer when it comes to making research, development and regulatory decisions along the route to a therapy.”

Patients and their organizations are increasingly contributing to all segments of the research pipeline. As such, scientists, industry, regulators and funders are incorporating patient input in their own decision making.

Funding what patients agree is valuable

Since the turn of the century, a number of government funding agencies have begun to incorporate patient perspectives in their funding decisions. For example, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) has launched a Strategy for Patient-Oriented Research (SPOR) Collaboration Grant program. Grants through SPOR are aimed at teams of researchers, clinicians and patients, with patients actively engaged in the design of research questions, defining objectives, collecting data and evaluating the results.

“I think funding opportunities that engage patients can be good for the research team,” says Vivian Choh, PhD, associate professor of optometry and vision science at Waterloo University in Ontario, Canada. “The scientists will be guided toward answering questions important to patients who may benefit from the work, which ultimately improves the communication between patients and researchers.”

In the U.S., the Department of Defense’s Congressionally Directed Medical Research Programs incorporate patients directly on their grant review panels. They serve as full voting members of the panel and help ensure that each research program focuses on directions with significant potential impact for the affected community.

Ireland is currently testing a program inviting Irish citizens with no scientific background to review research grants funded by the Health Research Board, the country’s primary research agency.

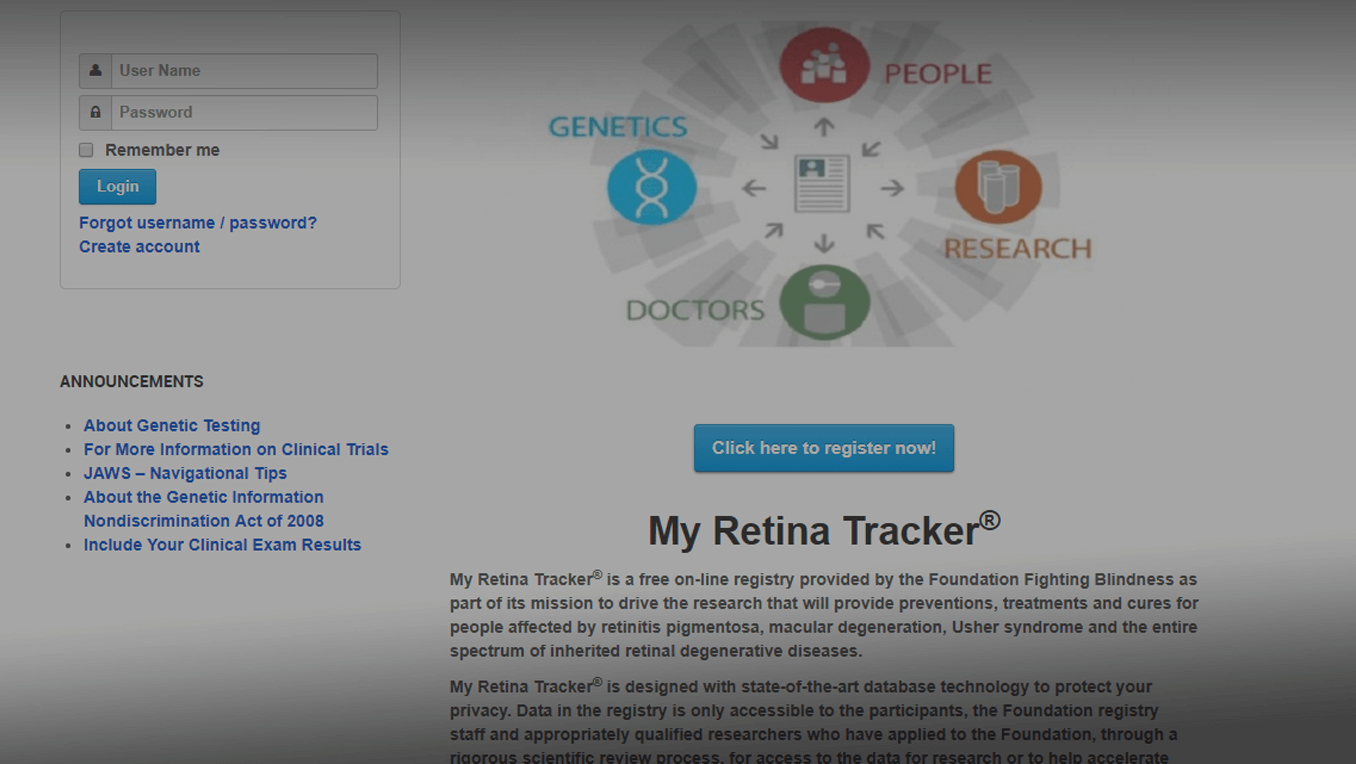

Building their own research tools Patient organizations have begun to organize their most valuable resource — information about those affected by the disease — into tools of value to researchers and drug developers. For example, Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) has developed a patient registry called “My Retina Tracker” for people affected with an inherited retinal dystrophy. The registry is piloting genetic testing to patients to identify the genetic cause of their declining vision. Participants are encouraged to update the information they share, including clinical exam data, to describe ongoing disease development. “My Retina Tracker provides a dynamic natural history — patients continually update their own records as to what they are experiencing,” says Steve Rose, PhD, chief research officer at FFB. “In this sense the registry is very much like a patient-reported outcome record.”

Patient organizations have begun to organize their most valuable resource — information about those affected by the disease — into tools of value to researchers and drug developers. For example, Foundation Fighting Blindness (FFB) has developed a patient registry called “My Retina Tracker” for people affected with an inherited retinal dystrophy. The registry is piloting genetic testing to patients to identify the genetic cause of their declining vision. Participants are encouraged to update the information they share, including clinical exam data, to describe ongoing disease development. “My Retina Tracker provides a dynamic natural history — patients continually update their own records as to what they are experiencing,” says Steve Rose, PhD, chief research officer at FFB. “In this sense the registry is very much like a patient-reported outcome record.”

“Companies are coming to us for this data to understand how many individuals there are who could benefit from potential treatments, and how can they enroll patients in their own clinical trials,” says Rose. “We have assisted over a dozen companies to date, saving them a significant amount of time and resources as they work toward developing future treatments for our patients.”

CRF has created the Choroideremia Biobank for basic researchers and industry partners interested in using the tissues and adult-derived stem cells donated by choroideremia patients. “CRF has leveraged the Biobank and other resources to attract more than $50 million in industry investment in choroideremia research and therapy development. We are currently working on a more robust choroideremia patient registry and a consolidation of natural history data,” says Wheelock.

Influencing the final decision

Should the people who stand to benefit from a newly developed treatment have a say in whether or not it gets approved for clinical use?

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which has final say on approval of drugs in the U.S., first confronted this question in the face of the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s. Patients, wanting to be heard and part of the process, wound up closing down the FDA headquarters in Rockville, Md., for a day by surrounding the building. Ongoing activities by the patient community led to the FDA Patient Representative Program. The Program is responsible for giving patients and primary caregivers a seat (and vote) on FDA Advisory Committees, an independent group of experts that provides influential advice on whether or not a treatment should be approved by the agency.

In the coming months, the FDA is expected to announce a new office to act as a central entry point for patient groups to the FDA. The office will likely be responsible for developing an agency-wide patient engagement policy, lowering the barrier patient organizations currently face in having their voice heard by the agency.

Are we at the point where patients are truly considered partners in the biomedical research community? Not yet, says Wheelock. “We have seen attitudes begin to change in the last few years, but there is still much to be done to achieve full partner status and recognition.”

Still, those driving research today may want to make room at the table for a patient perspective — and the resources they bring with them. MW